- BLOG

Why Can’t Travel Apps Handle Delivery Constraints?

Published: February 13, 2026

Route Optimization API

Optimize routing, task allocation and dispatch

Distance Matrix API

Calculate accurate ETAs, distances and directions

Directions API

Compute routes between two locations

Driver Assignment API

Assign the best driver for every order

Routing & Dispatch App

Plan optimized routes with 50+ Constraints

Product Demos

See NextBillion.ai APIs & SDKs In action

AI Route Optimization

Learns from Your Fleet’s Past Performance

Platform Overview

Learn about how Nextbillion.ai's platform is designed

Road Editor App

Private Routing Preferences For Custom Routing

On-Premise Deployments

Take Full Control of Your Maps and Routing

Trucking

Get regulation-compliant truck routes

Fleet Management

Solve fleet tracking, routing and navigation

Middle Mile Delivery

Optimized supply chain routes

Construction

Routes for Construction Material Delivery

Oil & Gas

Safe & Compliant Routing

Food & Beverage

Plan deliveries of refrigerated goods with regular shipments

Table of Contents

If travel apps can guide millions of people across cities every day, why do delivery teams still struggle to meet schedules, capacity limits, and customer commitments? The answer lies in the nature of the problem itself. Travel apps are designed to move individuals from point A to point B, while delivery operations must coordinate vehicles, time windows, loads, and compliance rules all at once. What seems like a routing challenge quickly becomes a complex planning exercise that navigation tools were never built to solve.

Continue reading to understand why travel apps fall short when delivery constraints enter the picture and what it takes to plan routes that actually work at scale.

Delivery routing is essentially a system-level planning problem. It involves coordinating a number of vehicles and drivers at a time, where the routing decisions of one driver influence other drivers in the same fleet. Routes are not solitary but are interdependent and are to be considered as a part of a larger operation plan and not as a trip.

Planning of effective delivery should be a combination of cost, time, compliance, and quality of service. Stop sequencing, vehicle assignment, and scheduling decisions cannot be made in reaction to what is happening on the road, but rather must be made before routes are run. Premeditation helps in ensuring that the routes are viable, adhering, and in line with the customer commitments at the very beginning.

Travel apps are optimized for mobility, not logistics. Their data structure, optimization objectives, and execution process are inherently out of sync with the constraint-intensive nature of delivery processes. The gaps below explain why delivery complexity breaks travel app routing.

Travel apps do not simulate vehicle-specific capacity characteristics, including weight capacity, volumetric capacity, pallet quantity, compartment separation, or stacking policies. Orders are considered abstract destinations and not physical loads, which have physical characteristics.

Since the capacity is not cumulatively followed along a route, travel applications do not allow vehicles to be overloaded or incompatible orders to be paired. This results in partial satisfaction, reassignments at the last minute, or vehicles being sent back to depots on the way. Routes may be perfectly drivable on the road network, but physically impossible to execute given real vehicle constraints.

Travel applications compute arriving time according to traffic conditions, yet they do not impose customer availability windows and contractual service-level agreements. Time windows are not considered as hard constraints when generating routes; they are just estimates.

This means that deliveries can no longer be prioritized in terms of service commitment and risk of penalty. Late arrivals cause SLA violations, customer dissatisfaction, and fines, whereas early arrivals cause wasted labor and idle time. Sequencing decisions made without time window logic do not match routes with actual delivery requirements.

Travel app routing does not include driver labor restrictions like shift start time, maximum driving hours, required rest breaks, and cumulative weekly limits. Routes are created without considering the legal or safety requirements of the work of drivers.

This exclusion enhances the chances of fatigue, violation of rules, and compulsory overtime. When routes are beyond the limits of allowance, dispatchers are left to manually intervene, and this poses operational risk and inconsistent compliance. In the absence of labor modeling, travel applications cannot ensure that a route is legally implementable.

Travel apps plan routes one request at a time. All routes are optimized in isolation, with no consideration of other vehicles, parallel routes, or shared constraints in the fleet.

This architecture does not allow workload balancing among drivers and vehicles. Certain routes are overutilized, and others are underutilized. It results in inefficient use of assets, higher fuel consumption, and increased labor expenses. The fleet-wide goals, like the reduction of total miles or the equalization of the route length, are impossible to reach without global optimization.

Travel apps are unaware of geographical operations like delivery area, service area, depot area, and preferred area of operation. Routes are created simply by the road networks as opposed to the organization structure.

Consequently, the routes can be made to traverse depots or territories that are not essential, which adds deadhead miles and inefficiency. Drivers are deployed to new territories, the predictability of routes is reduced, and team coordination becomes harder. Delivery networks lack structural efficiency when they grow without geographic control.

Here is how travel app architecture breaks down when exposed to real-world delivery constraints:

Travel applications are designed based on the request of a single traveler to get directions on a single trip. The routing requests are considered to be a single-origin, single-destination computation. There is no concept of chained stops, multi-leg execution, task dependency, or route continuation across time.

The routing requests are carried out individually in the routing engine. There exists no common state of operation among vehicles, users, and parallel routes. The system fails to simulate routes that interact in parallel, congestion due to fleet behavior, and the use of common infrastructure.

The optimization function is normally constrained to a minimization of travel time, distance, or approximate arrival time. Cost functions are unidimensional and scalar and do not have multi-objective optimization, i.e., time, cost, reliability, and operational risk balancing.

Routing services are stateless APIs. After a route has been calculated and returned, the system has no memory of the route. No cumulative or anticipatory optimization is possible, as past choices, current paths, and future engagements are not taken into account.

At the core, travel apps rely on road network graphs using algorithms such as Dijkstra, A*, or contraction hierarchies. Nodes signify intersections, and edges signify road segments where the weights are updated dynamically on the basis of the speed of traffic, incidents, and previous trends.

The routing graph continually has its edge weights altered by traffic sensors, probe vehicle data, and incident reports. Such changes are optimized to the existing environment and do not trickle down to higher-level planning, reasoning, or execution viability.

User interaction triggers routing, which is handled as a request-response transaction that is a synchronous operation. It has no batch planning step, no horizon-based optimization window, and no rolling re-optimization cycle between multiple routes.

Travel applications do not combine constraint satisfaction solvers, mixed-integer linear programming, or metaheuristic engines. The routing engine is not concerned with hard constraints, soft constraints, penalty functions, and feasibility checks.

The architecture does not have vehicle, driver, load, skills, and equipment domain models. The routing decisions are based on space information only, and there is no allocation of resources, tracking of capacity, or compatibility.

Time is considered as an output and not a constraint. Arrival times are approximations that are calculated after routing and are not implemented as scheduling limits. There is no modeling of service duration, dwell time, or appointment adherence.

The system lacks a system-wide goal like the minimization of total miles, workload balance, or the minimization of emissions. All the routes are locally optimized, and the results are globally suboptimal when applied to a large number of vehicles.

Once navigation begins, deviations such as delays, route changes, or failures are not fed back into a centralized optimization model. The system does not learn from execution outcomes to influence future routing decisions.

The travel apps are horizontally scaled to support millions of independent users. Although it can be scaled technically, logical isolation of requests does not allow coordinated user or resource optimization.

The entire system is geared towards short response time, low latency, and ease of interaction. The architecture and design choices are immediate and usable rather than constraint handling, validity of feasibility, and operational robustness.

Here is how delivery-first route optimization platforms solve the limitations of travel apps and handle real-world delivery constraints at scale:

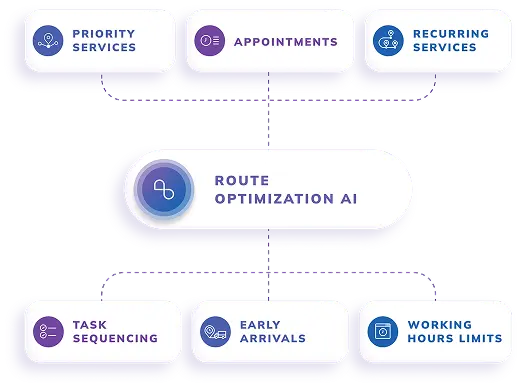

Intelligent routing platforms are engineered to solve combinatorial optimization problems that travel apps are not designed to address. While travel apps rely on shortest-path algorithms optimized for speed and latency, route optimization systems use constraint programming, heuristics, and metaheuristics to evaluate millions of route permutations. They explicitly model vehicle capacity, service times, driver labor rules, time windows, zones, and depot logic. This allows them to produce routes that are not only efficient on the map but also physically, legally, and operationally executable, something travel apps fundamentally cannot guarantee.

Travel apps operate at the execution layer, reacting to traffic conditions after a trip has started. Intelligent routing platforms operate at the planning layer, where decisions are made before vehicles are dispatched. They convert orders, resources, and constraints into a coordinated plan that anticipates conflicts instead of correcting them mid-route. This eliminates common travel-app failures such as early arrivals, missed delivery windows, overloaded vehicles, and driver overtime, which reactive navigation cannot resolve.

Travel apps calculate routes independently, with no shared state or awareness of other vehicles. Intelligent routing platforms optimize at the fleet level, treating all vehicles, drivers, depots, and stops as part of a single system. This enables global objectives such as workload balancing, total mileage minimization, fuel optimization, and equitable route duration. Fleet-wide optimization prevents scenarios where one driver is overloaded while another is underutilized, a structural limitation of travel app routing.

Delivery-first platforms include domain models that travel apps lack entirely, such as vehicles with capacity attributes, drivers with labor rules, loads with compatibility constraints, and territories with service boundaries. They support hard constraints, soft constraints, penalty costs, and feasibility checks during route generation. This architecture allows multi-objective optimization, balancing cost, time, reliability, compliance, and service quality simultaneously, rather than optimizing only for distance or ETA as travel apps do.

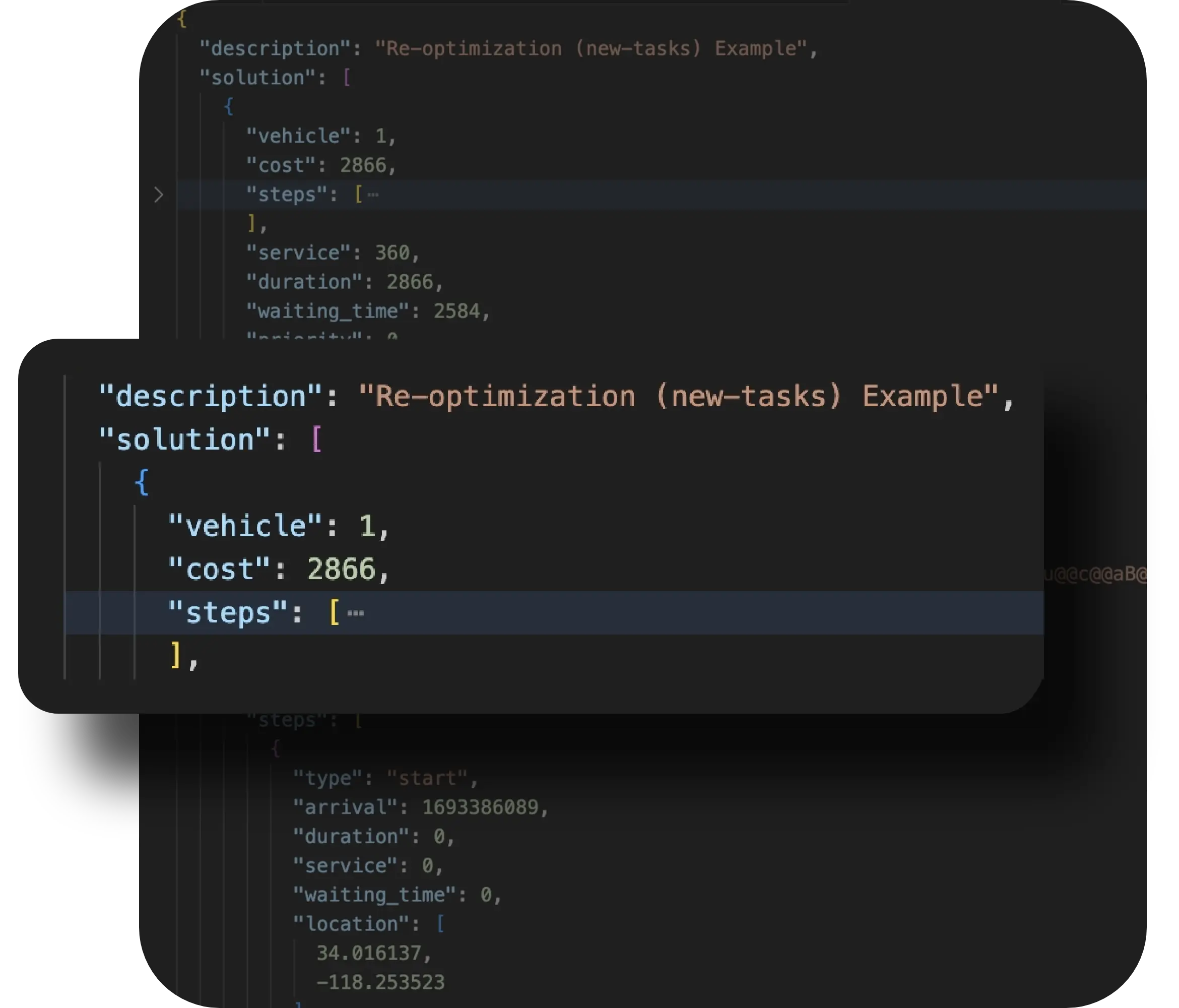

Platforms like NextBillion.ai close the structural gaps left by travel apps by providing AI-powered, constraint-aware routing as a core planning capability. Instead of treating routing as a stateless navigation request, they embed optimization into enterprise workflows through APIs that support fleet-wide planning, dynamic re-optimization, and real-time adaptability without breaking constraints. This transforms routing from a driver aid into a strategic operational system capable of scaling with delivery complexity.

A regional delivery company must complete 120 deliveries in one day using 8 vehicles operating from a single depot. Each vehicle has a fixed weight and volume capacity. Nearly half the customers require delivery between 10:00 AM and 1:00 PM, and all drivers must finish within legally defined working hours.

Using a travel app, routes are created by manually grouping stops and then optimizing each route for the fastest path. On the road, issues emerge quickly. Two vehicles exceed capacity and must skip stops. One driver reaches several customers too early and waits idle, while another misses delivery windows due to poor sequencing. Dispatchers intervene repeatedly, reassigning stops and extending driver shifts, increasing cost and operational risk.

With delivery-optimized planning, all orders and constraints are evaluated together before dispatch. Stops are assigned based on capacity, delivery windows, and driver availability. Routes are sequenced to meet time commitments, workloads are balanced across vehicles, and compliance is ensured upfront. Execution becomes predictable, with fewer interruptions, consistent service levels, and lower operational overhead.

Modern delivery operations require agile technologies that go far beyond navigation. Unlike travel apps, these systems are designed to plan, validate, and optimize deliveries under real-world constraints such as capacity, time windows, labor rules, and fleet-level efficiency. Each technology plays a distinct role in transforming routing from reactive navigation into structured operational planning.

Here is a concise comparison of the core technologies used in delivery-first routing.

Technology | Primary Purpose | What It Handles Well | Why Travel Apps Fail Here |

AI Route Optimization Engines | Fleet-wide route planning | Capacity, time windows, labor rules, zones, depots | No constraint modeling or global optimization |

Constraint Programming | Feasibility validation | Hard limits, delivery rules, SLA enforcement | Travel apps do not validate feasibility |

Heuristics and Metaheuristics | Large-scale optimization | Thousands of stops, multi-vehicle routing | Shortest-path algorithms do not scale |

Traffic Intelligence Integration | Realistic planning | Accurate ETAs during planning and execution | Traffic used only for reactive rerouting |

Dynamic Re-Optimization | Operational resilience | Delays, cancellations, new orders | Reactive changes break constraints |

Fleet-Level Cost Functions | System efficiency | Workload balance, mileage, fuel optimization | Local route optimization only |

API-First Routing Platforms | System integration | OMS, TMS, dispatch, driver apps | Stateless, isolated routing requests |

Domain Modeling Layers | Operational realism | Vehicles, drivers, loads, territories | No resource abstraction |

Compliance Engines | Legal and safety control | HOS, regional driving limits | Compliance ignored entirely |

Multi-Depot Optimization | Network efficiency | Depot selection, deadhead reduction |

Reactive routing is concerned with changing routes once they have been started, which is normally as a result of a change in traffic, delays, or a disruption. The strength of travel apps in this model is that they re-compute routes in real time, although without reconsidering the constraints on delivery, workload balance, or compliance.

Planned optimization, however, plans routes prior to execution by modeling capacity, time windows, labor regulations, as well as service commitments. This proactive planning makes the routes viable, legal, and economical from the very beginning. It also eliminates the necessity to correct them in the middle and further reduces the operational problems that can only be resolved by proactive adjustments.

Here is a table that highlights the key differences between reactive routing and planned optimization in delivery operations:

Factor | Reactive Routing (Travel Apps, Manual Adjustments) | Planned Optimization (Route Optimization Software) |

Primary Objective | Respond to conditions during execution | Design feasible routes before execution |

Planning Timing | Occurs after routes are already in progress | Completed before routes are dispatched |

Optimization Scope | Single route or driver at a time | Entire fleet optimized as one system |

Constraint Handling | Limited to traffic and road conditions | Models capacity, time windows, labor, zones, and rules |

Vehicle Capacity Awareness | Not supported | Fully enforced during planning |

Time Window Enforcement | Informational ETAs only | Hard constraints built into routing logic |

SLA and Priority Handling | Not considered | Embedded and validated before execution |

Driver Labor Compliance | Ignored | Enforced automatically |

Multi-Vehicle Coordination | Not possible | Native fleet-wide coordination |

Workload Balancing | Uneven and manual | Balanced across vehicles and drivers |

Handling Disruptions | Ad hoc rerouting | Controlled re-optimization within constraints |

Impact of Mid-Route Changes | High disruption to plans | Minimal disruption with preserved feasibility |

Cost Control | Reactive and unpredictable | Predictable and optimized |

Scalability | Breaks as the stop count grows | Scales to thousands of stops |

Operational Risk | High risk of violations and failures | Low risk due to pre-validated plans |

Role in Delivery Stack | Execution aid for drivers | Core planning intelligence |

Here is how route optimization bridges the gap between simple navigation and real-world delivery operations.

NextBillion.ai applies highly sophisticated optimization algorithms to consider millions of routing options and take into consideration the real-world delivery constraints. The engine also takes into account capacity, time windows, driver shifts, geography, and traffic conditions to come up with efficient and executable routes.

The system enables delivery crews to coded business and operational regulations into routing logic. During the planning, constraints like the size of vehicles, the amount of load to be carried, service times, restrictions by zone, and depot restrictions are implemented to ensure that routes are viable before the actual execution of the routes.

NextBillion.ai does not optimize routes separately, but instead, it optimizes fleet-wide and depot-wide. The assignments of stops are made to the vehicles and depots to balance the workloads, minimize the overall fleet mileage, and optimize the use of assets at the system level.

NextBillion.ai uses traffic intelligence and past travel history in the computation of the routes. This allows more accurate ETAs in the planning process and routes to be reliable as the actual conditions vary.

In case of delays, cancellations, and new orders, the platform recalculates routes in an intelligent way without violating capacity constraints, time windows, compliance regulations, or workload balance. This guarantees a stable operation throughout the day without the need to be operated by hand.

NextBillion.ai is an API-first platform that is easily connected to order management systems, fleet management software, dispatch applications, and driver applications. This enables the organizations to incorporate the sophisticated routing intelligence into the existing workflows without interfering with the operations.

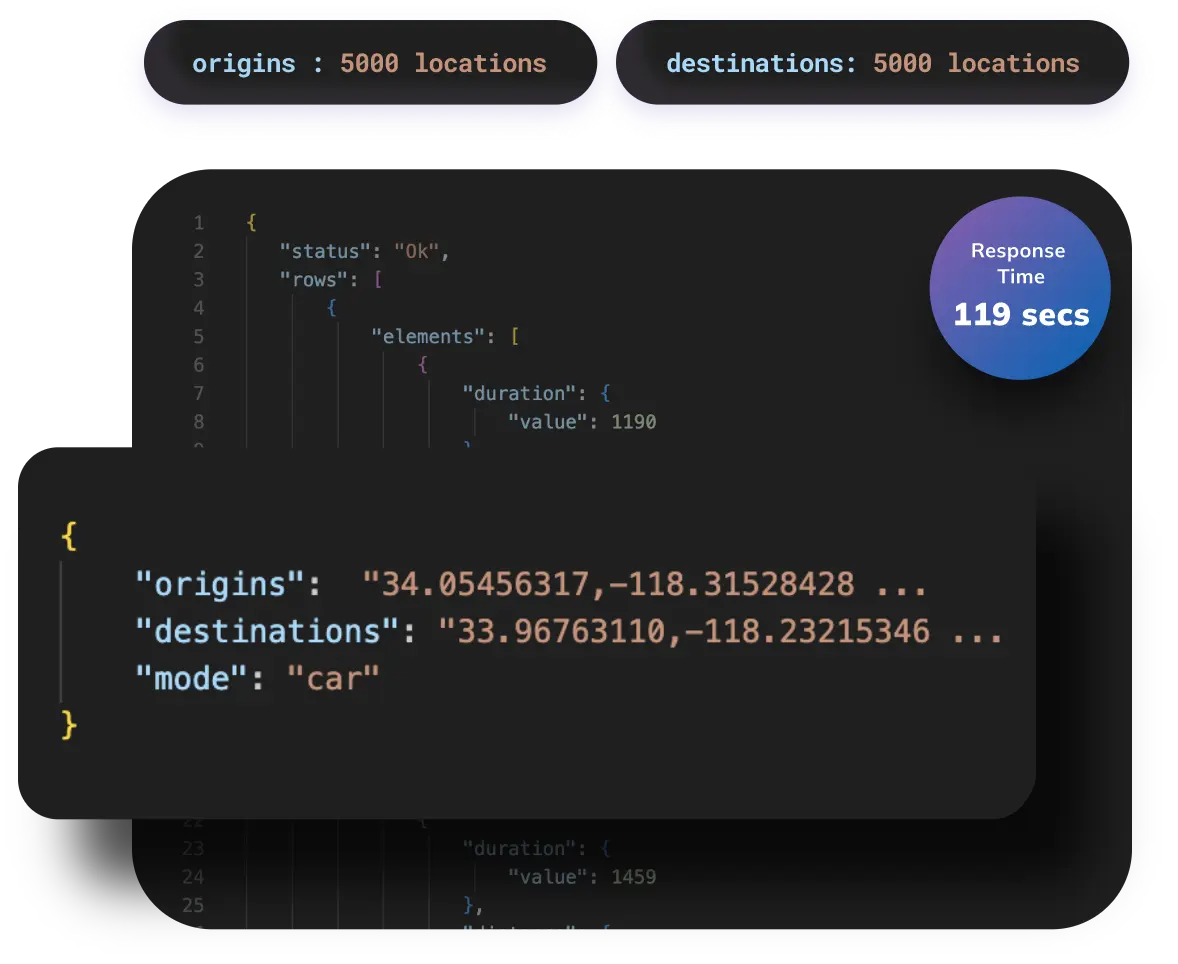

Beyond basic routing, our platform offers complementary APIs like large distance matrix generation (supporting up to 5000×5000 matrix sizes) and driver assignment to enable comprehensive logistics planning from first mile to last mile.

Travel apps excel at guiding individuals through road networks, but delivery operations demand far more than navigation. As the scale of deliveries increases, routing becomes a system-level planning problem, which has to consider the capacity of the vehicles, time windows, labor compliance, service commitments, and fleet-wide efficiency. The architectures of travel apps are deliberately lightweight, stateless, and user-focused, which do not fit in the environment of constrained delivery.

In the absence of premeditated optimization, delivery crews experience increased expenses, compliance threats, and irregular service. The gap is filled by specific route optimization software, which creates viable, legal, and scalable delivery plans prior to the commencement of execution.

Find out how NextBillion.ai can transform the delivery teams to next-level operational intelligence, as opposed to navigation. At NextBillion.ai, we offer AI-based, constraint-aware routing and enterprise-ready APIs, allowing scalable, compliant, and cost-effective delivery operations to be developed to meet the complexity of the real world. Connect with us to know more.

Travel apps would require a fundamental architectural redesign to support capacity, time windows, labor rules, and fleet-wide optimization, which goes far beyond incremental feature additions.

Constraints normally become inevitable when operations involve more than a few vehicles and more than one stop per day, particularly when there are customer time limits or driver labor regulations.

Interdependent routes, real-time changes, and complex constraints cannot be reliably modelled using spreadsheets. Errors and planning time increase exponentially with the increase in stop count.

Travel APIs can be used to compute navigation and estimate the ETA, but not to compute constrained delivery routes that need feasibility checks and optimization at the fleet level.

Ignoring constraints results in increased fuel consumption, overtime compensation, SLA fines, underutilization of vehicles, and frequent manual interventions, which increase operating expenses

Bhavisha Bhatia is a Computer Science graduate with a passion for writing technical blogs that make complex technical concepts engaging and easy to understand. She is intrigued by the technological developments shaping the course of the world and the beautiful nature around us.